Queen Introduction – Balling the Queen Bee

Beekeepers have struggled with how best to introduce a new queen into a beehive for ages – whether they’re wanting to requeen an existing colony of honeybees or place a new queen into a newly created colony. When a colony of honeybees is presented with a new queen, the bees’ first instinct is to act aggressively towards her. Since her pheromones do not match the hive, the bees see the new queen as an intruder and will instinctively come after her.

If a newly introduced queen is not protected during the introduction period, it is almost guaranteed that the colony will kill her. The worker bees will approach her aggressively –quickly grabbing onto her and not letting go. First, one bee starts this behavior, then another, and another – before long, honeybees will surround the queen, grabbing on and not letting go. This is known as balling.

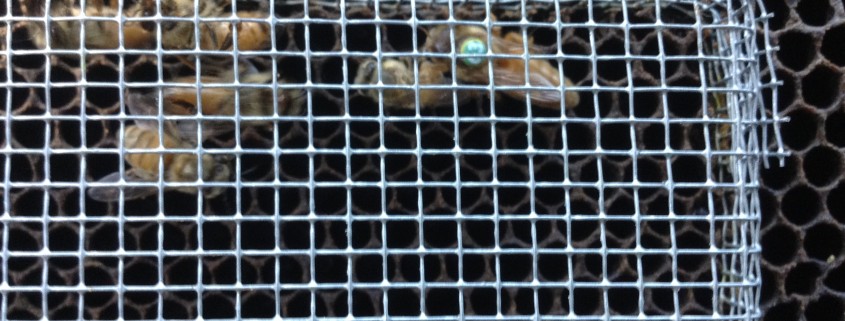

When a newly introduced queen is being balled, she is in trouble. The worker bees will grab at her body parts, and very possibly, sting her to death. This is why queen honeybees are almost always introduced to a new colony while inside some sort of cage. The cage protects the queen from an almost certain onslaught and gives her a safe place to hide.

Even with a cage, the bees will still attempt to ball the queen. However, with a cage in the way, the most that the bees can do is grab onto the cage and attack it, sparing the queen inside. Over time, the worker bees gradually cease balling the cage – one by one giving up and allowing the queen a little reprieve, while she is still safely protected inside of the cage.

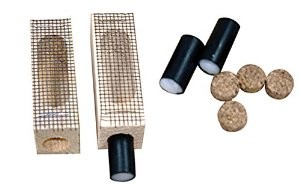

While this is all happening, the colony’s worker bees are eating through the candy release tube in the cage. Well before the bees have worked their way through the candy, the balling bees have given up and have gone back to their usual work within the hive.

Even once the queen has been released from her cage, she still is somewhat at risk for renewed balling, until she actually starts laying eggs. This is why most experienced beekeepers, including us at Wildflower Meadows, always advise leaving a colony alone for a full week after the introduction of a new queen. Only when she is laying eggs can a newly introduced queen be truly considered as accepted by the colony, and relatively free from the risk of being balled.