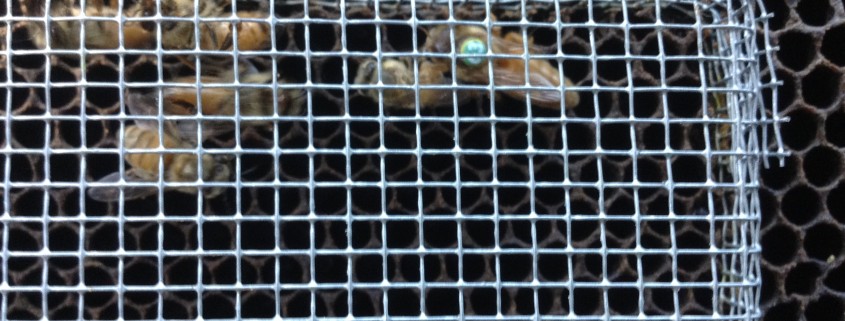

What is it about queen bees that are so attractive to worker bees? When we took the photo shown above, we had just prepared six queens from the day’s harvest for introduction into our own colonies. Note how the workers can’t seem to show enough love to the queens. These attendants were so fixated on the queens that they traveled inside our truck like this without us even needing to put a lid on the box! The workers simply had no desire to fly away nor to stop attending to the queens.

When we prepare shipments of bulk boxes, it is never a problem getting attendant bees motivated to stay and care for the queens. A quick shake of a frame of bees into the box produces more than enough workers willing to stay with, and attend to, the queens the whole time they are in transit.

The queen pheromone is so powerful that bees will even drop out of the sky to investigate a box of queens! When we deliver queens to UPS, we have been cautioned by the office staff not to arrive prior to 4:30pm, as any earlier causes curious bees to fly into their customer service center, potentially frightening UPS customers.

Inside the hive is no different. Worker bees can immediately identify the presence of a queen, as well as the lack of a queen. The method of this attraction is through a pheromone known as the “queen pheromone”. The purpose of the queen pheromone is to signal to a hive that a queen is present and that she is recognizable.

A pheromone is a chemical that is secreted by a member of a species that can be used to control the behavior of another member of the same species. Imagine how much love we could receive if we humans had a pheromone as powerful as the “queen pheromone”!

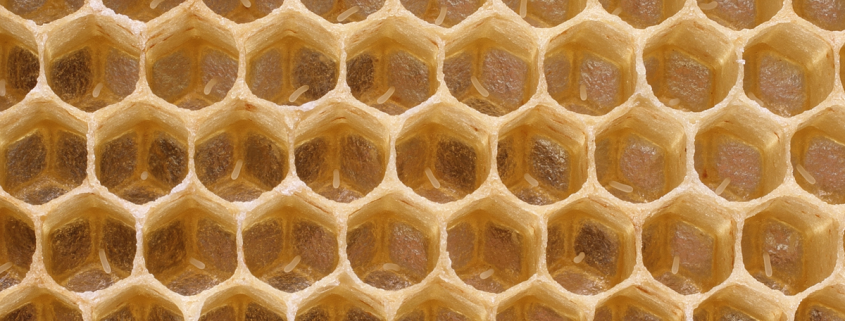

Queen pheromone is secreted near the head of the queen in an area above her jaw known as the mandibular. Her secretions make her identifiable to all bees inside the hive; workers, drones, and possibly other queens. The workers spread this pheromone throughout the hive using their antennae. If this pheromone is absent, the colony will soon recognize its absence and will know that they are queenless. They will then begin to construct emergency queen cells to raise a new queen.

Not only can a hive measure the presence, or absence, of queen pheromone, but it also able to measure the level of it. A dip in the level of queen pheromone indicates that the queen could be beginning to fail. This will often cause a colony to begin raising replacement queens for supercedure of the current queen.

It is well known that overcrowded bees are more likely to swarm than bees with ample space. However, some beekeepers believe that the overcrowding of bees itself inhibits the transfer of queen pheromone throughout the colony, therefore causing the colony to raise replacement queen cells in anticipation of a swarming event.