Eighty Years Later: A Tribute To O.W. Park

Today we take for granted the idea that beekeepers can prevent American Foulbrood and other infectious diseases with antibiotics. Back in the early 20’th century, however, there existed no effective way to control infections. Penicillin had not even been discovered until 1928, and it was a number of years later before the first antibiotics became commercially available.

With the absence of antibiotics, beekeepers of the time struggled mightily with American Foulbrood, an infectious disease that routinely killed beehives (and still does today). The only way that beekeepers of the time could control this deadly disease was to burn infected hives and equipment to keep the disease from spreading. Even to this day, a sizable percentage of beekeeping books still speak of the need to burn equipment that is infected with American Foulbrood. That this message of burning infected equipment carries forward all the way into 2016 is a testimony as to how severe this rampant and deadly disease was – and especially with the advent of resistant antibiotics – still is.

It is easy today for all of us to take for granted the concepts of “resistant bees,” “hygienic behavior,” “treatment free beekeeping,” etc. These are commonly used terms, and relatively well-known concepts in today’s beekeeping world – especially when it comes to queen rearing. It is hard to imagine that eighty years ago, in the mid 1930’s, these concepts did not exist. Beekeepers weren’t even aware that bees could be selectively bred to establish these desirable traits in honeybees.

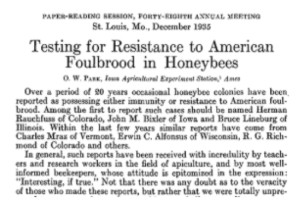

In 1935, a visionary beekeeper, O.W. Park, noticed that certain colonies seemed to be resistant or immune to American Foulbrood. He had an idea: What if honeybees could be bred to be resistant to American Foulbrood, and the disease could be controlled with the genetics of the bees themselves? Starting with 25 strong and apparently resistant colonies, along with six control colonies, Mr. Park, along with his associates, set out to test this theory. He then purposely exposed and infected all 31 colonies with infected American Foulbrood larvae!

What then happened? All of the six control colonies, and many of the 25 resistant colonies died. But, amazingly, seven of the resistant colonies survived. In 1936 Mr. Park then bred a second generation of colonies from this “survivor stock,” which proved to show an even greater level of resistance in the next generation. In the process, Mr. Park pioneered the concept of identifying resistant bees, and selectively breeding bees for disease resistance. He also proved that this concept works, and can yield real and positive results.

2016 marks the eightieth anniversary of this landmark study on disease resistance in honeybees. A full eighty years later, beekeepers continue to carry on in the shadows of the visionary, O. W. Park.